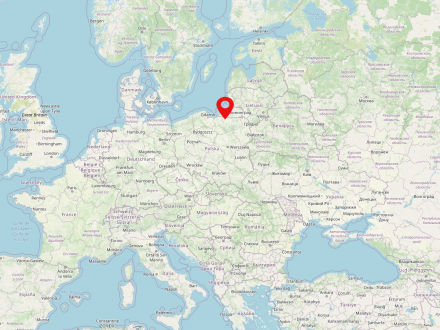

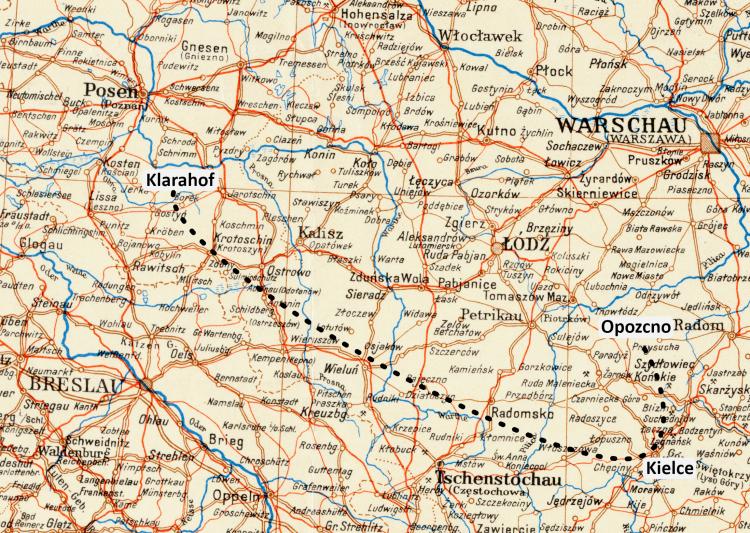

At dawn the wagons were opened and the gendarmes disappeared. Someone stepped down onto the platform, and others followed. We stood on a platform thickly covered with snow, not knowing what to do next. Mom went to the station building and there she learned from the railroad workers that we were in Opoczno.1

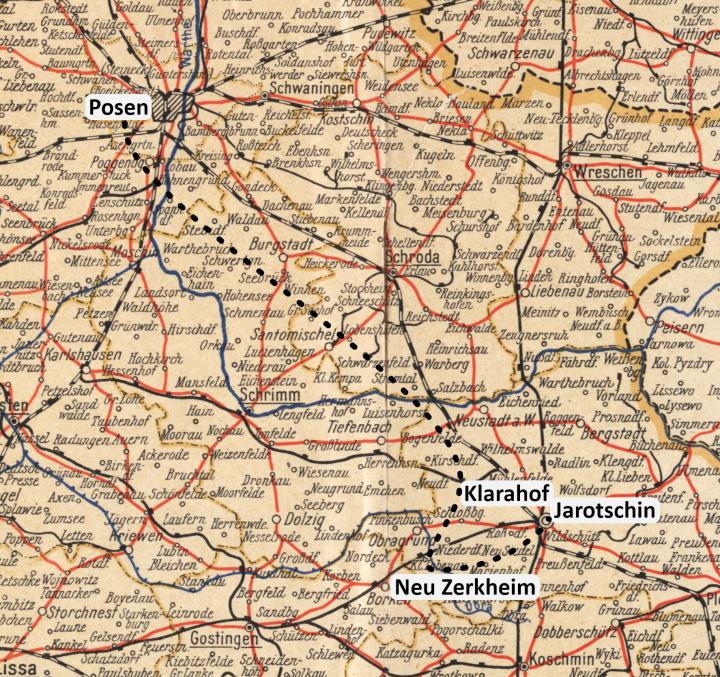

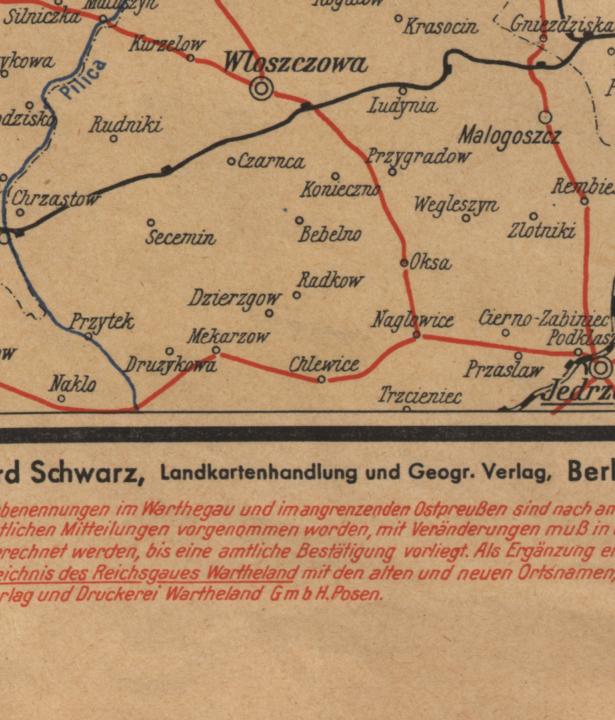

Poznań is a large city in the west of Poland and the fifth largest city in the country with a population of over 530,000. The trade fair and university city is located in the historic landscape of Wielkopolska and is also the capital of today's voivodeship of the same name. Already an important trade center in the early modern period, the city first fell to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793 as part of the newly formed province of South Prussia. After a short period as part of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), Poznań rejoined Prussia after the Congress of Vienna as the capital of the new Province of Posen. From 1919, the city belonged to the Second Polish Republic for two decades, before it was occupied by the Wehrmacht in 1939 and became part of the German Reichsgau Wartheland (the so-called Warthegau). The almost six-year occupation period was characterized by the brutal persecution of the Polish and Jewish population on the one hand - tens of thousands were murdered or interned in concentration and labor camps -, and the resettlement of German-speaking population parts in the city and surrounding area on the other. In early 1945, Poznan was conquered by the Red Army and became part of the Polish People's Republic. One of the most important events of the post-war period was the workers' uprising in June 1956, which was violently suppressed.

Wielkopolska is the name of a historical landscape in the center and southwest of the present Polish state, which is also considered the historical heartland of Poland. In the southwest, Wielkopolska borders on the historical landscape of Silesia, in the west on the historical parts of the Mark Brandenburg, and in the north and northeast on Pomerelia and Kujawy. Important cities are Poznań and Gniezno.

After Wielkopolska came to Prussia in 1815 as the so-called "Grand Duchy of Poznań" and later "Province of Poznań", the name of the region as "Poznań Land" also became common.

The name and size of today's Wielkopolska Voivodeship, which is populated by approximately 3.5 million people and has an area of almost 33,000 square kilometers, are both derived from the region's historical landscape.

Poznań is a large city in the west of Poland and the fifth largest city in the country with a population of over 530,000. The trade fair and university city is located in the historic landscape of Wielkopolska and is also the capital of today's voivodeship of the same name. Already an important trade center in the early modern period, the city first fell to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793 as part of the newly formed province of South Prussia. After a short period as part of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), Poznań rejoined Prussia after the Congress of Vienna as the capital of the new Province of Posen. From 1919, the city belonged to the Second Polish Republic for two decades, before it was occupied by the Wehrmacht in 1939 and became part of the German Reichsgau Wartheland (the so-called Warthegau). The almost six-year occupation period was characterized by the brutal persecution of the Polish and Jewish population on the one hand - tens of thousands were murdered or interned in concentration and labor camps -, and the resettlement of German-speaking population parts in the city and surrounding area on the other. In early 1945, Poznan was conquered by the Red Army and became part of the Polish People's Republic. One of the most important events of the post-war period was the workers' uprising in June 1956, which was violently suppressed.

Kielce is a large city in southeastern Poland and also the capital of the Holy Cross Voivodeship (województwo świętokrzyskie). The city has more than 190,000 inhabitants, is an important industrial and commercial city and the seat of several universities.

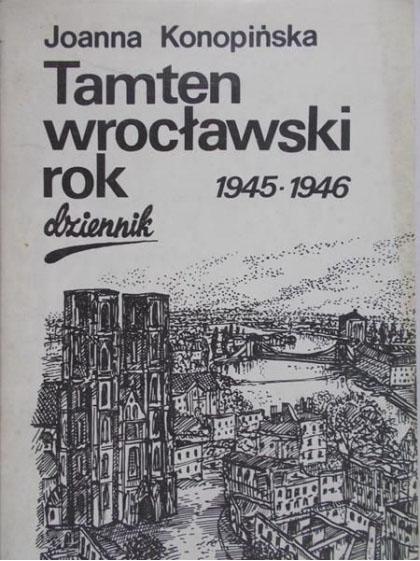

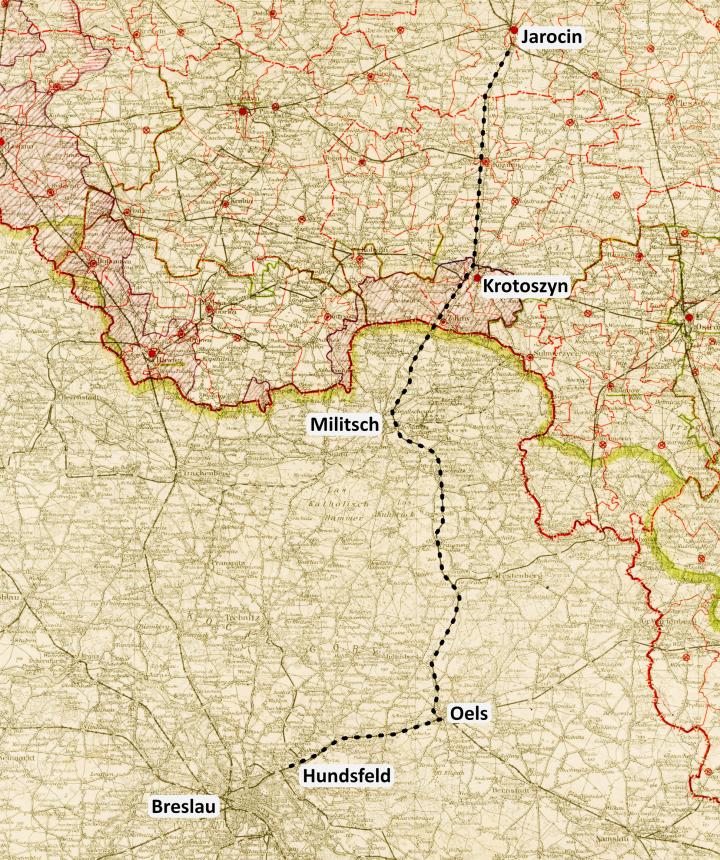

Wrocław (German: Breslau) is one of the largest cities in Poland (population in 2022: 674,079). It is located in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship in the southwest of the country.

Initially under Bohemian, Piast and at other times Hungarian rule, the Habsburgs took over the Silesian territories in 1526, including Wrocław. Another turning point in the city's history was the occupation of Wroclaw by Prussian troops in 1741 and the subsequent incorporation of a large part of Silesia into the Kingdom of Prussia.

The dramatic increase in population and the fast-growing industrialization led to the rapid urbanization of the suburbs and their incorporation, which was accompanied by the demolition of the city walls at the beginning of the 19th century. By 1840, Breslau had already grown into a large city with 100,000 inhabitants. At the end of the 19th century, the cityscape, which was often still influenced by the Middle Ages, changed into a large city in the Wilhelmine style. The highlight of the city's development before the First World War was the construction of the Exhibition Park as the new center of Wrocław's commercial future with the Centennial Hall from 1913, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2006.

In the 1920s and 30s, 36 villages were incorporated and housing estates were built on the outskirts of the city. In order to meet the great housing shortage after the First World War, housing cooperatives were also commissioned to build housing estates.

Declared a fortress in 1944, Wrocław was almost completely destroyed during the subsequent fightings in the first half of 1945. Reconstruction of the now Polish city lasted until the 1960s.

Of the Jewish population of around 20,000, only 160 people found their way back to the city after the Second World War. Between 1945 and 1947, most of the city's remaining or returning - German - population was forced to emigrate and was replaced by people from the territory of the pre-war Polish state, including the territories lost to the Soviet Union.

After the political upheaval of 1989, Wrocław rose to new, impressive heights. The transformation process and its spatial consequences led to a rapid upswing in the city, supported by Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004. Today, Wrocław is one of the most prosperous cities in Poland.

Wielkopolska is a voivodeship in the west of Poland. The capital of the voivodeship is Poznań. Wielkopolska is inhabited by 3.5 million people. Besides Poznań, the largest cities are Kalisz/Kalisch, Konin and Leszno.

Silesia (Polish: Śląsk, Czech: Slezsko) is a historical landscape, which today is mainly located in the extreme southwest of Poland, but in parts also on the territory of Germany and the Czech Republic. By far the most significant river is the Oder. To the south, Silesia is bordered mainly by the Sudeten and Beskid mountain ranges. Today, almost 8 million people live in Silesia. The largest cities in the region are Wrocław, Opole and Katowice. Before 1945, most of the region was part of Prussia for two hundred years, and before the Silesian Wars (from 1740) it was part of the Habsburg Empire for almost as many years. Silesia is classified into Upper and Lower Silesia.

We were taken via Ostrów Wielkopolski, Czestochowa, Kielce, Skarżysko-Kamienna. The train stopped constantly and stood in the field for several hours. It was not heated. The night was over and so was the everlasting day, and in the middle of the following night the train stopped at a nameless station.

At dawn the carriages were opened and the gendarmes disappeared. Someone was the first to descend onto the platform, and others followed. We stood on a platform thickly covered with snow, not knowing what to do next. Mom went over to the station building and there she learned from the railroad workers that we were in Opoczno."2

„As early as February, right after the front passed Kielce, Mama went to Panienka with Maryla and cousin Janek Bąkowski. Since there was no train service at that time, they had to walk most of the way. [...] it was not until mid-March that I set out for Panienka with my friend Ewa Chodźko, who had offered to accompany me on the journey, which lasted four days with interruptions. [...] The house in Panienka was completely empty. Only the furniture from the bedroom and part of the kitchen utensils remained - the rest of the house furnishings Fischer gave to the district administrator in Yarochin. Father grieves most for the paintings, which also disappeared. Allegedly, though the news has not yet been verified, part of them was seized by the Polish authorities in the district office and taken to the museum in Pozna? [...] In the farm buildings there was yawning emptiness. At the time of our arrival in Panienka there were a few dozen cows in the barn, but a few days ago Soviet soldiers drove the livestock to Mieszków. All that remained were two oxen and a limping cow.“3

Lithuania is a Baltic state in northeastern Europe and is home to approximately 2.8 million people. Vilnius is the capital and most populous city of Lithuania. The country borders the Baltic Sea, Poland, Belarus, Russia and Latvia. Lithuania only gained independence in 1918, which the country reclaimed in 1990 after several decades of incorporation into the Soviet Union.

Latvia is a Baltic state in the north-east of Europe and is home to about 1.9 million inhabitants. The capital of the country is Riga. The state borders in the west on the Baltic Sea and on the states of Lithuania, Estonia, Russia and Belarus. Latvia has been a member of the EU since 01.05.2004 and only became independent in the 19th century.

For a few days Uncle Walenty Galiński, owner of the neighboring Bielejewo estate, has been staying with us in Panienka. After the war he happily returned to his estate, but after a week the People's Police came and he was ordered to leave Bielejewo. Tomorrow our furniture will be brought, which was given to us by Fischer the District Administrator in Yarochin. At last we will be able to furnish the house, and will no longer have to live all in one room and lie on the bare floor on straw mattresses.5

East Prussia is the name of the former most eastern Prussian province, which existed until 1945 and whose extent (regardless of historically slightly changing border courses) roughly corresponds to the historical landscape of Prussia. The name was first used in the second half of the 18th century, when, in addition to the Duchy of Prussia with its capital Königsberg, which had been promoted to a kingdom in 1701, other previously Polish territories in the west (for example, the so-called Prussia Royal Share with Warmia and Pomerania) were added to Brandenburg-Prussia and formed the new province of West Prussia.

Nowadays, the territory of the former Prussian province belongs mainly to Russia (Kaliningrad Oblast) and Poland (Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship). The former so-called Memelland (also Memelgebiet, lit. Klaipėdos kraštas) first became part of Lithuania in 1920 and again from 1945.

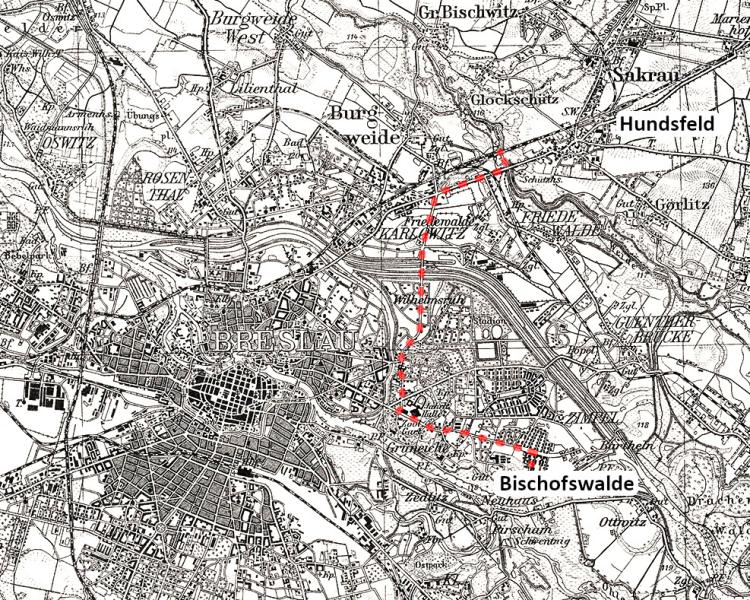

About a kilometer after the station [Hundsfeld] the train stopped. Continuing the journey turned out to be impossible because the bridge over the river was torn down. Only with difficulty could we make our way out of the wagon. In puddles of water on a large swampy meadow stood wagons; hundreds of different kinds of wagons: children's, garden, wooden, metal wagons with wheels or without, and also bicycles. When some passengers got out, others rushed in with their looted booty: carpets, bedding, and whatever they could pack on the wagons.[...] Most of the travelers went straight on Hundsfelder Street [today Bolesława Krzywoustego]. We turned left into Friedewalder Street [today Aleksandra Brücknera] and Kopernikus Street [today Jana Kochanowskiego], because on these streets we could get to Bischofswalde [obecnie Biskupin] the fastest via the eastern parts of the town [...].6

German Translation: Dariusz Gierczak (Polish-German)

English translation: William Connor

Map montage: Laura Gockert

Editing: Christian Lotz