Dedicated to the memory of Eszter Gantner z"l

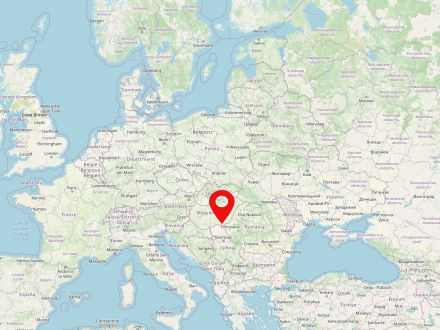

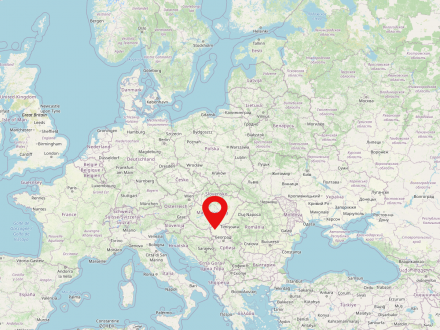

Szeged is the third largest city in Hungary and is located near the southern border of Hungary. Hungary's border with Serbia is just outside the city. In the 14th century, Szeged was an important strategic point in southern Hungary, especially in the context of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. The city also played an important role in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. In July 1849, it was the last seat of the revolutionary government. After the First World War, Hungary lost its southern territories to Serbia, which meant that Szeged lost some of its importance as a regional centre in Hungary.

Csongrád-Csanád is located in southern Hungary, on the Tisza River, on the border with Serbia and Romania. It is bordered by the Hungarian counties of Bács-Kiskun, Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok and Békés. The administrative centre of Csongrád-Csanád County is Szeged.

Bačka or Bácska is a geographical and historical area in the Pannonian Plain, bordered on the west and south by the River Danube and on the east by the River Tisza. It is shared between Serbia and Hungary. The larger part of the area is located in the Vojvodina region of Serbia, and Novi Sad, the capital of Vojvodina, is located on the border between Bačka and Syrmia. The smaller northern part of the geographical area lies within Bács-Kiskun county in Hungary.

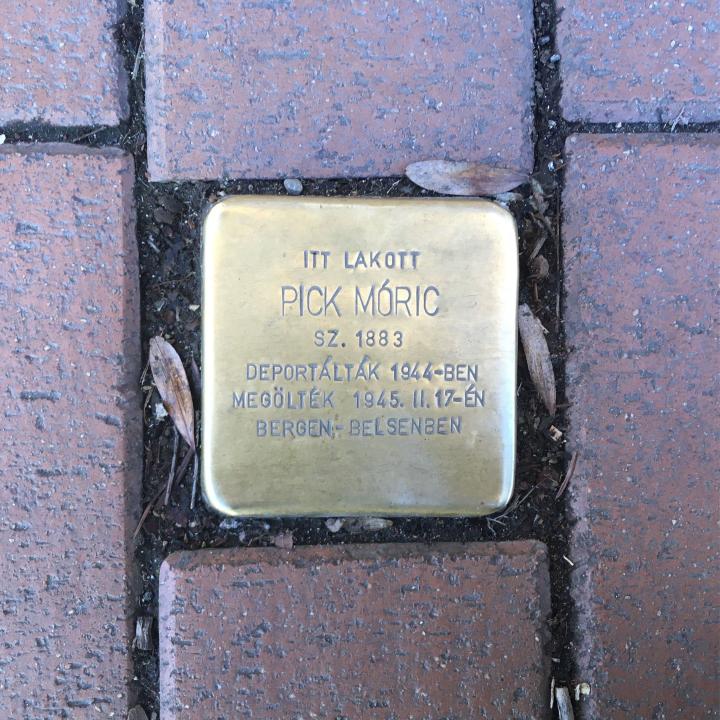

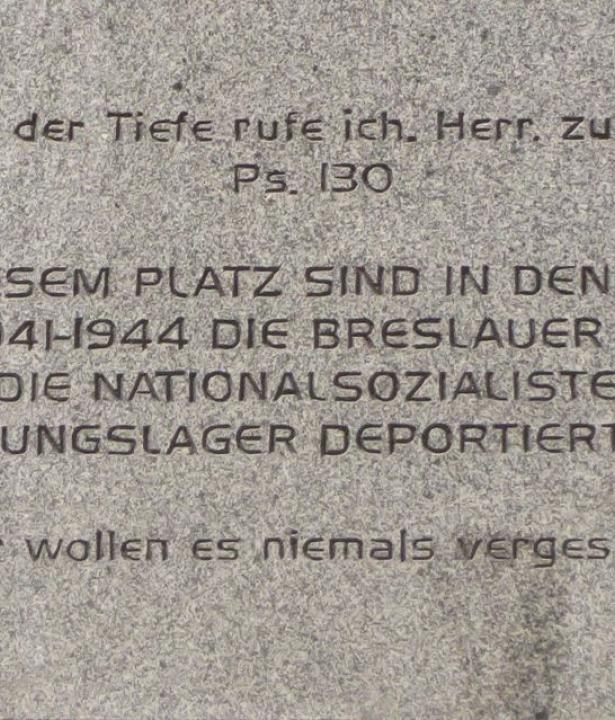

The New Synagogue of Szeged, a prominent European synagogue, was built in 1899-1903 by renowned architect Lipót Baumhorn (1860-1932). After WWII, the synagogue hall was transformed into a Holocaust commemoration site, and five smaller Holocaust memorials were erected in the Jewish cemetery, located in the outskirts of Szeged. In 2018, a statue symbolizing Jewish-Christian relations during the Holocaust was inaugurated in front of the cathedral. Stumbling stones and wall plaques also commemorate the Holocaust, as does the newly launched commemorative website.

• The Randegg Memorial is the largest monument honoring Holocaust victims in the cemetery. It is the final resting place for 99 Jews from Szeged and nearby cities. On April 15, 1945, during a march from the camps of Stangental and Kerschenbach to Mauthausen Concentration Camp, 100 Jews were tragically murdered in Randegg. Survivor Adolf Glück managed to escape from under the bodies of fallen victims. The corpses from Randegg were reburied in a joint grave in Szeged in 1947, symbolizing the cruel fate of the deportees. In March 1948, the Jewish community took the initiative to have a memorial stone to mark their remains.5 The Randegg Martyrs' Monument, commemorating the 99 victims, was inaugurated in June 1950.6 In 2022, when the name tables on the grave were counted, it turned out that there are a total of 100 names. Thus, further research is needed to reconstruct the identities of the victims.

Footnotes

Literature

- Ábrahám, Vera: Szeged zsidó temetöi. Szeged 2016.

- Bede, Márton: Szegeden felavatták a Szabadság téri emlékmű fordítottját. (eds.): 444. 2014. (last access: 2023-08-17)

- Bohus, Kata: Mártírünnepségek a háború után. (eds.): Szombat. 2022. (last access: 2023-08-17)

- Frojimovics, Kinga: Tömegsír exhumálások Ausztriában a Holokausztot követöen. A szegedi zsidó áldozatok újratemetése. In: Régió 24, 2. p. 22-30.

- Horváth, Rita: The Role of the Survivors in the Remembrance of the Holocaust. Memorial monuments and Yizkor books. In: Friedman, Jonathan C. (eds.): The Routledge History of the Holocaust. London 2010 . p. 472-483.

- Kónya, Judit: Pusztulás és gyász: vallásjogi problémák (1945-1949). In: Régió 24, 2. p. 7-21.

- Laczó, Ferenc: Caught between Historical Responsibility and the New Politics of History. on Patterns of Hungarian Holocaust Remembrance. In: Mitroiu, Simona (eds.): Life Writing and Politics of Memory in Eastern Europe. New York 2015 . p. 185-201.

- Varga, Anna: Emlékmüvet állított az egyházmegye a holokauszt szegedi áldozatainak. (eds.): Szegedma. 2014. (last access: 2023-08-17)

- Zombori, István: Függelék. Az 1941-45 között elhurcolt és meghalt szegedi zsidók névsora. In: Zombori, István (eds.): A szegedi zsidó polgárság emlékezete. Szeged 1990

Citation

- Dóra Pataricza: Places of commemoration of the Shoa in Szeged, Hungary. In: Copernico. History and Cultural Heritage in Eastern Europe. URL: https://www.copernico.eu/en/link/64de46e616e8c2.85688014 (2024-05-19)

- Published under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (illustrations see picture credits)