Czechoslovakia was a state existing between 1918 and 1992 with changing borders and under changing names and political systems, the former parts of which were absorbed into the present-day states of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Ukraine (Carpathian Ukraine, already occupied by Hungary in 1939, from 1945 to the Soviet Union). After 1945, Czechoslovakia was under the political influence of the Soviet Union, was part of the so-called Eastern Bloc as a satellite state, and from 1955 was a member of the Warsaw Pact. Between 1960 and 1990, the communist country's official name was Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (abbreviated ČSSR). The democratic political change was initiated in 1989 with the Velvet Revolution and resulted in the establishment of the independent Czech and Slovak republics in 1992.

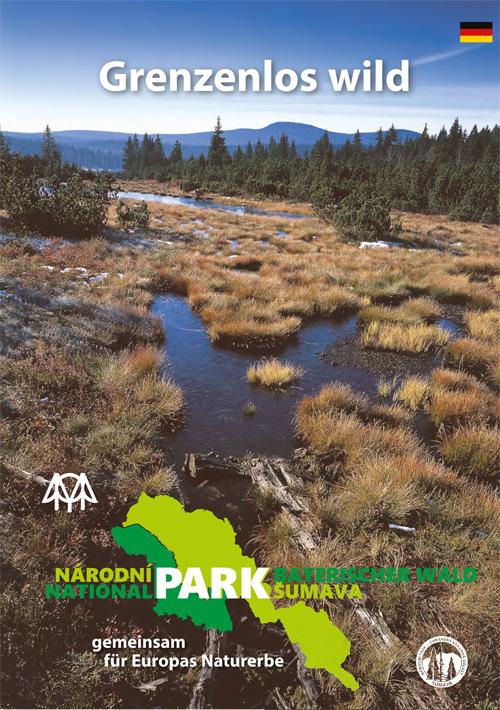

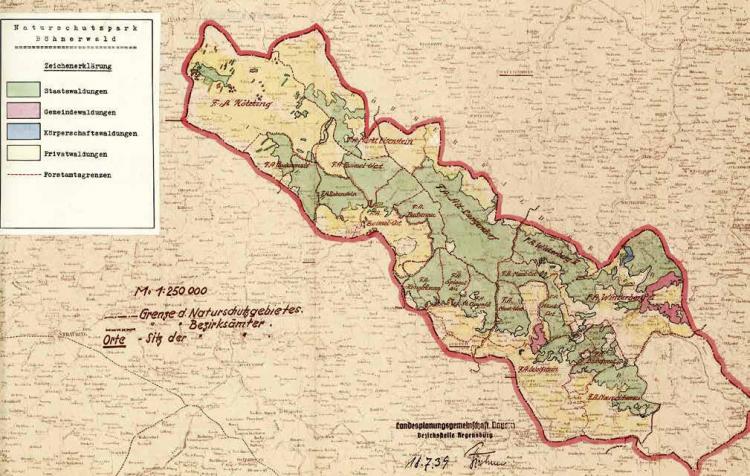

The history of the mountainous border region includes both aspects: unified ecology as well as political division. If we focus too heavily on the political border, we run the risk of ignoring the commonalities and the geographic and ecological coherence of the two "parts." At the same time, the slogan “wilderness without borders,” which takes no heed of the man-made border, is too simplistic. It ignores the formative significance that the state border had and still has for the area of the Bavarian Forest and Šumava. The history of nature conservation in the area is, to a large extent, also a history of the border: a history of overcoming and maintaining it, and of its changing shape, perception, and meaning. The following snapshots from the last one hundred years of cross-border nature conservation in the Bavarian Forest and Šumava show that the reality of the border played an important role for nature conservationists, precisely in the moments when they tried to overcome it.

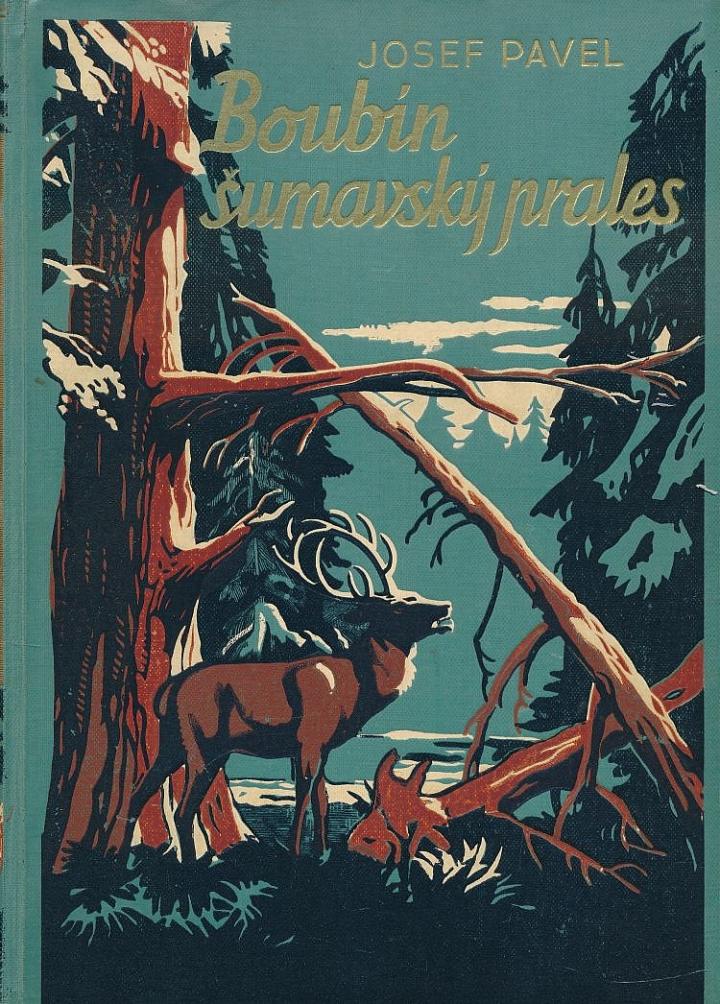

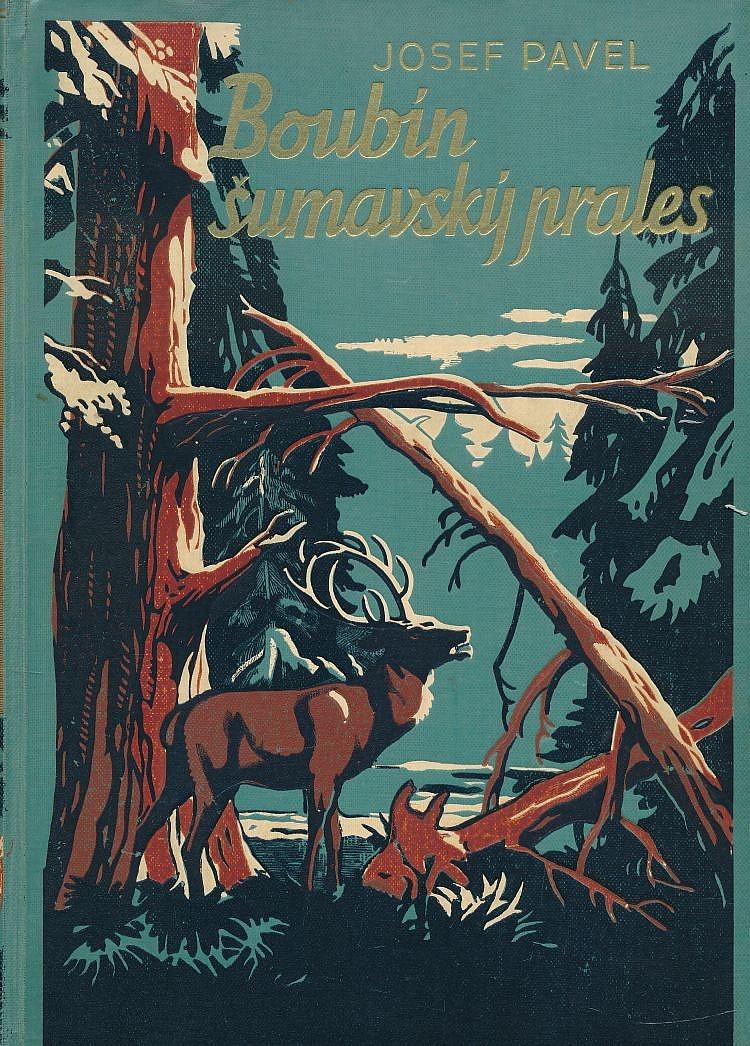

Der Boubín ist ein 1362 m hoher Berg in der Tschechischen Republik. Er liegt im Böhmerwald.

Sušice is a town in the Klatovy district in the Pilsen region of the Czech Republic. Its Czech name comes from sušit (to dry - referring to the drying of gold sand) and alludes to the former gold mining. Today the town has a population of around 11000.