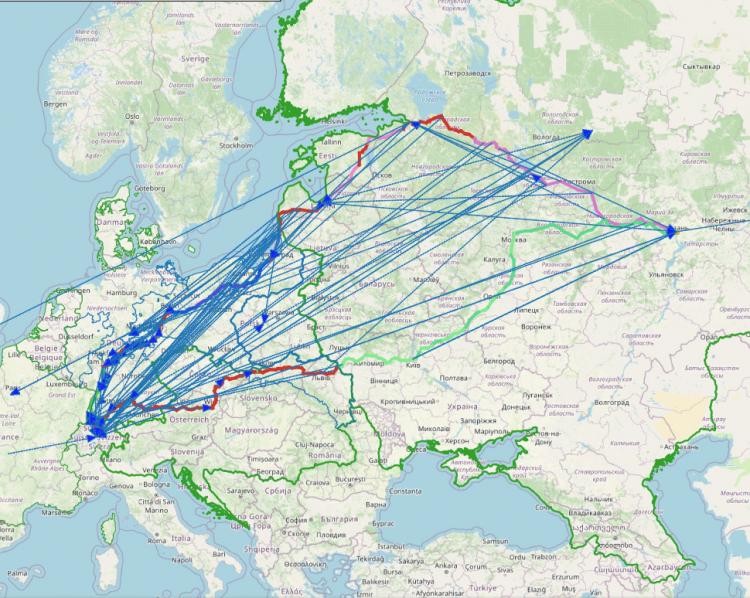

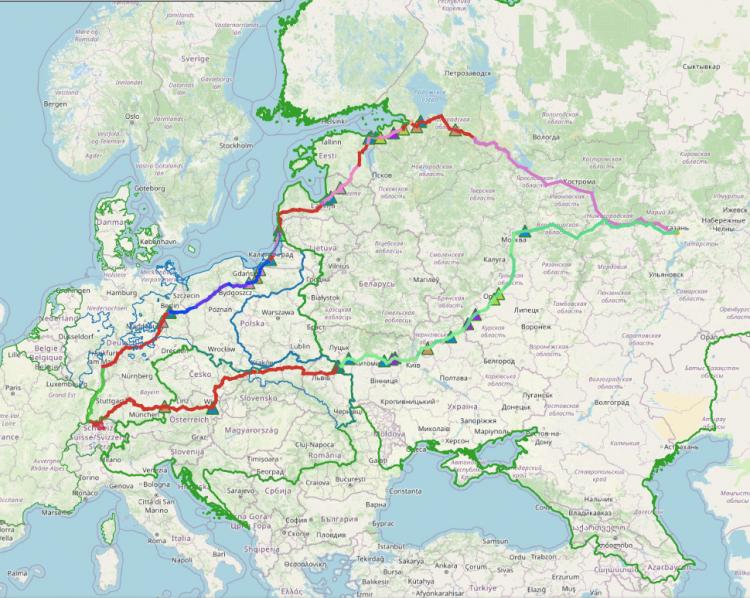

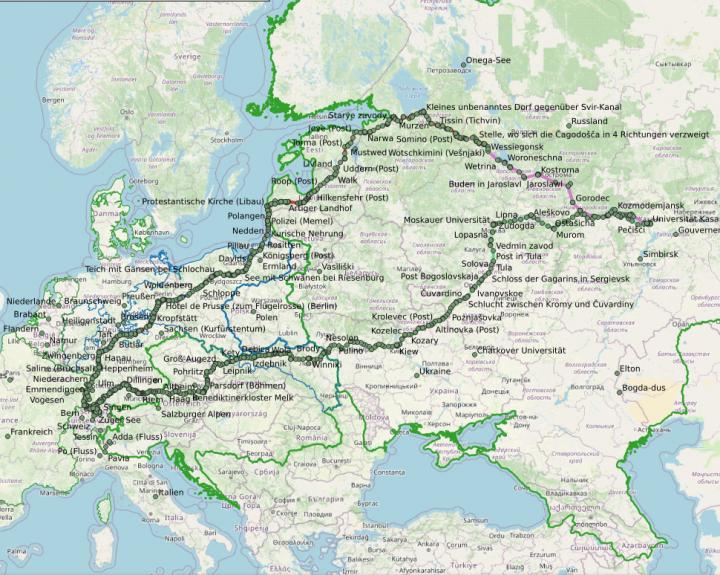

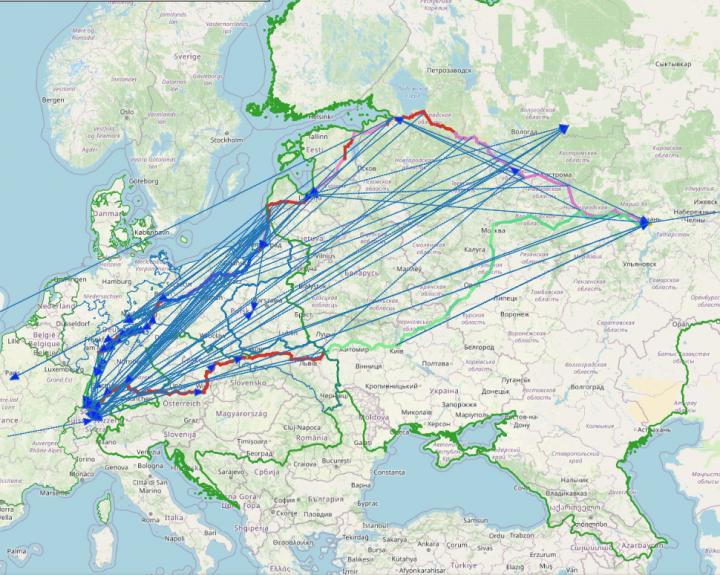

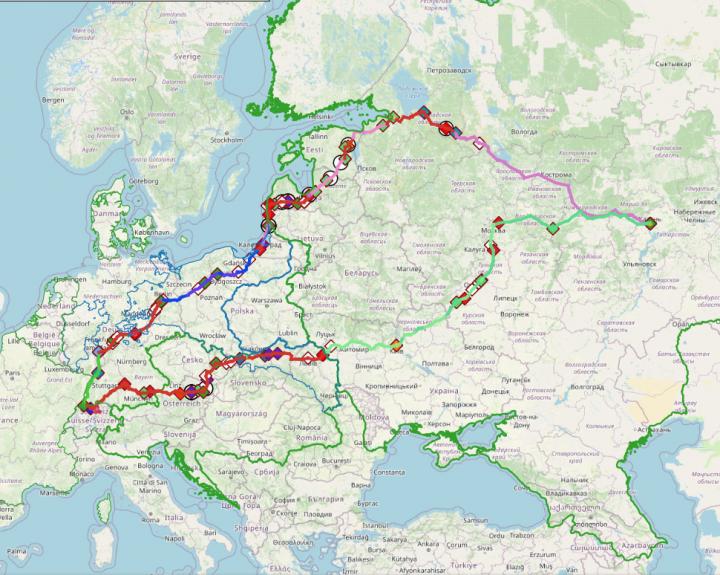

Bronner came, as mentioned, from Höchstädt on the Danube. He entered the Benedictine monastery of St. Cross in Donauwörth at an early age. But his real life began only after his second escape to Switzerland at the end of 1793. As a supporter of the Enlightenment, and thanks to his dexterous pen, he attained an important post in the administration during the period of the Helvetic Republic established by France (1797-1803) which, however, also brought him many hostilities after the victory of the reaction. He spent the following years as a teacher at the newly built high school in Aarau Canton with a poor, and above all, insecure salary. According to his three-volume biography from 1795-1797, his literary enthusiasm for Switzerland at that time, his friendship with the Zurich poet and patriot Salomon Gessner and his family, and his acquaintance with numerous members of Zurich's educated liberal elite, contributed to this. The numerous comparisons of travel impressions with Switzerland, which are displayed on the map with lines (if you activate "Connections") and which are always in favor of Switzerland, prove this impressively.

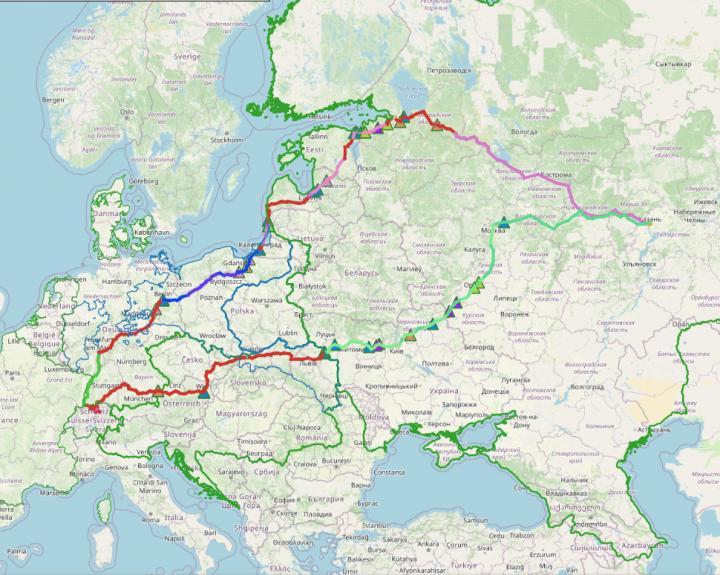

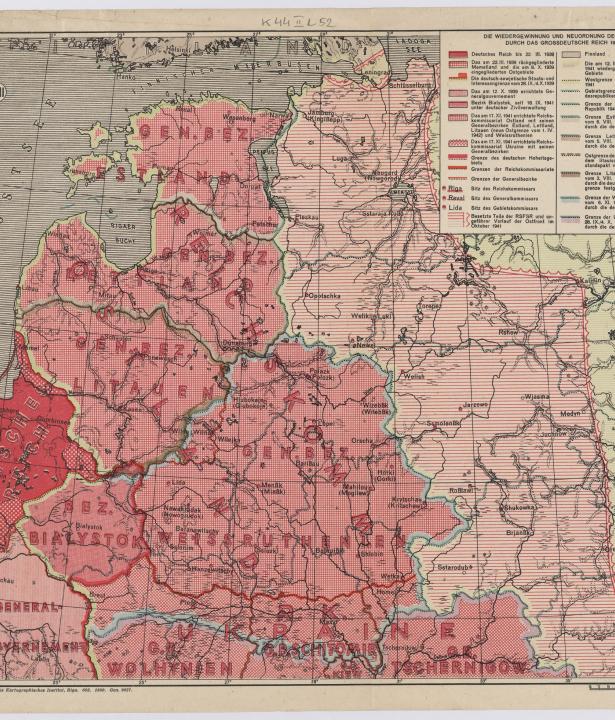

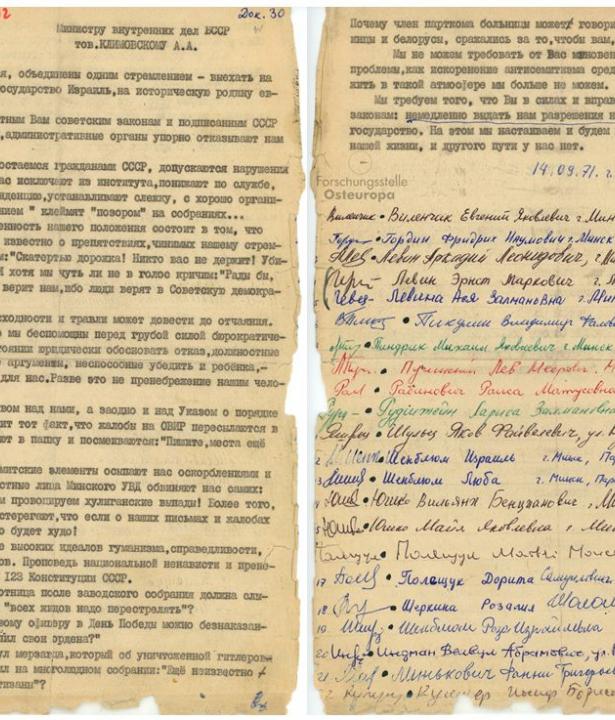

It is striking that Bronner's original home on the upper Danube and in "Swabia" hardly appears in comparisons. Understandably, Bronner repeatedly refers to places he has already traveled through, whereby the backward-looking comparisons (albeit predominantly with Switzerland) become more frequent after crossing the Russian border. In this context, "Switzerland" stands–in accordance with the clichés of the time–for fertile landscapes and a highly developed agriculture, while "Germany" stands for higher culture. The reality described was somewhat different. In Prussia, Bronner repeatedly gets upset about arbitrariness of officials–this, too, not without the influence of contemporary stereotypes, but besides that also as a consequence of the desolate state of the country after the defeat against Napoleon. In Russia, Bronner notes with displeasure the constant need to pay bribes ("gifts") (map: activate "points with officials"; it is recommended to deactivate the connections afterwards). Already at the border beyond Memel he mentions his initial helplessness against this system. The perfection to which it had been developed is impressively experienced on the journey home, when Bronner describes how a Jewish innkeeper guides him through the Russian export customs at Radziwiłłów/Radziviliv. Incidentally, the map shows that bribes did not stop entirely in Austria, either. Bronner's image of Poland (beginning in the Polish partitions of Prussia) was consistently negative. His negative image of Jews was linked to his encounter with the culturally alien Eastern Jews and their concentration in the Russian settlement regions but could be partially corrected by experience.

As an element of foreignness, Bronner adds serfdom in the Baltic states– again recognizably under the influence of European discourse. Almost everything that he comments on negatively there, especially the poverty of the rural population, Bronner associates with serfdom. In the interior of Russia, on the other hand, it is only marginally an issue for him.

Even St. Petersburg, behind the facades of the magnificent houses, no longer makes such a European and civilized impression on Bronner. His description of the house corridors is likely to awaken memories in many readers of their own observations from late and even post-Soviet times.

Beyond the capital, Bronner got deeper and deeper into the Russian province. The descriptions of how he was robbed by coachmen and even threatened by peasants during quarrels make a mockery of the predictions of the St. Petersburg informants that Bronner would be in good hands with honest "real" Russians there. Nevertheless, he apparently believed this himself in the beginning.

On the whole, Bronner paints a picture of a culturally inferior world in the East, but without using this word. Having said that, it begins at the Saxon-Prussian border and, as he turns homewards, it gradually fades away after crossing the Russian-Austrian border in Galicia, and only really ends at Simbach on the Bavarian border.